Dealing with the disappointment of a bad training session

This article aims to deal with a very specific time in a person’s life, the sad feels immediately after a bad training session (not a workout, a term which implies you do no train for anything in particular)

Don’t worry friend, all gains have not been lost!

To illustrate this point I will use myself as an example. A few months back I was due to bench press 140kg for 4 sets of 4 reps. Going into the session I knew it was very doable. Set one went well, set 2 was very tough but I got 4 reps. Then came set three…everything fell apart! After a slow second rep, I descended for my third and got stuck on the chest. I tried to make up the missed volume by adding extra sets but in reality, my head was gone, I was out of the game. Then we moved onto Overhead press. More missed reps! The same thing happened on Dumbbell Bench Press and at this point I was just fed up and left.

Then a few days later I was due to hit 88kg for 4 sets of 2 on the overhead press. After what felt like a very, very heavy first set of two it started happening again. I started missing reps again. Then my shoulder started bugging me (probably from my degraded technique). Then I started warming up for bench press with the goal of hitting 4 sets of 7 with 120kg. However, after my second warm up set I decided to stop. I had realised that my head was not in the game and that continuing was doing me more harm than good. So I abandoned the session, did some low-load blood flow restriction training for 30 minutes and got the hell out of there!

At this point after having two bad sessions it’s easy to feel frustrated, feel like all gains are lost, FOREVER! And you should feel like that, because you know you’ll never be in the gym ever again after that, you won’t ever have another opportunity to make up for those bad sessions. In case you can’t tell I’m being extremely sarcastic. The reality is you will be back in the gym again soon and you’ll probably smash those numbers sooner than you might think.

4 days later I repeated that second session described above. I hit 90kg for 4 sets of 2 on the overhead press and 120kg for 4 sets of 8 on the bench! 2 weeks later I repeated the first training session described above and got 4 sets of 4 reps on the bench press (with the potential to do a fifth set) and didn’t miss anymore reps on the other exercises in the rest of the session.

What changed?

Surely I didn’t get that much stronger in a few days. Well, in the aftermath of a bad session, you have to analyse where you went wrong. According to Elite FTS owner, Coach, former Powerlifter and Bodybuilder Dave Tate, missed lifts always come down to any one (or a combination of ) 3 factors: Physical, Technical or Mental. We will use this as a framework for why my sessions were going poorly!

1. Physical:

- Did you eat enough today and yesterday?

- Did you perform any activities in the last 48 hours that may have left you in a fatigued state coming in to this session?

- Did you get to bed early enough and did you get enough high quality, uninterrupted sleep last night?

- When did you last train and have you any lingering muscle soreness or fatigue in general?

- Have you grinded much in your training sessions recently (i.e. have you recorded a lot of RPE’s in the 9-10 range) (Zourdos et al. 2015)?

- How stressful is your life lately? Are any of your relationships with any of your family members, work colleagues or your significant other causing you to stress out lately?

- Is there anything going on in your life that is causing you a lot of stress (e.g. money worries, a loved one very sick, work very stressful this week etc.)?

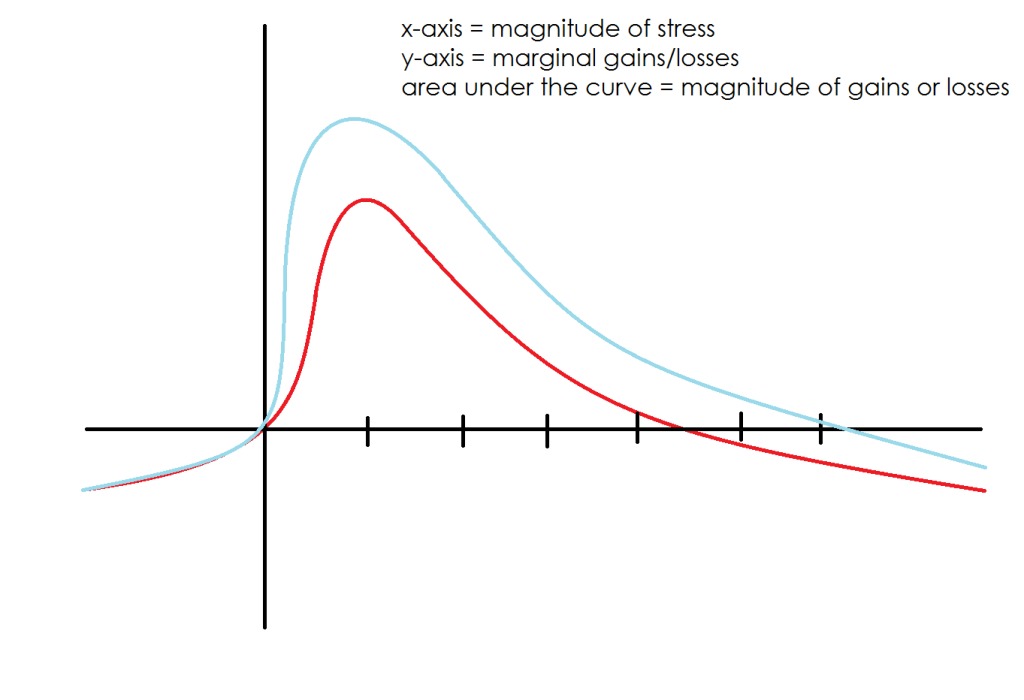

These are all the questions you have to ask at this point. And one stressful event that eats into your recovery ability can have a knock-on effect on another factor. For example, you may be well able to recover from a heavy deadlift session and able to train the bench press the next day no problem, under normal, low stress conditions. However when things get hectic at work, to the point you get stressed out and you start to miss meals accidentally. Then you accidentally snap at your friend who means well but just manages to say the wrong thing to you at the wrong time (Edit, Arthur really hurts our feelings when he's hungry). Then you land yourself in a big, stressful argument, which serves to further deplete your recovery sources. Then you go and do that brutal deadlifting session. Think you’re in an optimal state to recover before your next session now? This is illustrated brilliantly in Figure 4.6 below. Which is taken from Greg Nuckols and Omar Isuf’s recent e-book “The science of Lifting” (highly recommended by the way, they’re much more intelligent than me).The blue line represents recovery capabilities under low stress conditions, whereas the red curve represents recovery capabilities under stressful (i.e. compromised) conditions.

2. Mental:

- Have you been looking forward to this session or do you not even want to be in the gym today (this can be indicative of over-reaching)?

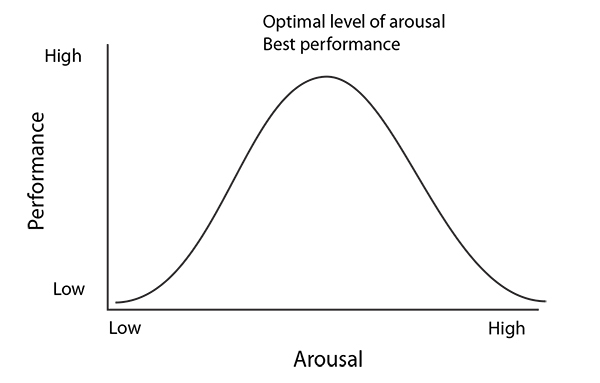

- Was your arousal level optimal before this session/set (see Figure 1)?

Figure 1 - Yerkes-Dodson Inverted U-Theory of optimal arousal levels for a given task

- Were you overthinking the lift before you attempted it?

- Had you in your head, 100% convinced yourself you were going to get it?

- Was your mind elsewhere (the stress inducing factors mentioned previously for example)?

- Did you draw on a memory of a past performance that did not go well for you (i.e. did you think of another previously missed lift)?

- What was your training environment like? Were you training on your own or were you with others who support you and help motivate you to lift better?

3. Technical:

- Did you change your usual bar speed, particularly on the eccentric (i.e. if you went much slower on your descent for some reason)?

- Was your breathing/bracing off?

- Was your bar path off? Why? (For example sometimes I can bring the bar down too low on my chest and/or over-tuck my elbows if I get nervous on a bench press)

- Was something not kept tight enough (e.g. core, legs, upper back)

- (Note: This is a key example of why it’s crucial to video your sets, and from an angle that provides as much feedback on the movement as possible).

Analysis:

On reflection, that week of poor training was accompanied by some very hectic days at work and some nights of poor sleep. With me being someone who pushes hard regularly and leaves little room for error, something even as small as that can put me off. I also noticed that when I was lifting the bar out of the rack on the bench press that I was losing upper back tightness. Finally, and this last one may be related to nerves but my bar path was very inconsistent particularly on the way down (the eccentric portion) from rep to rep. So I also addressed this in the next session.

Now in my own scenario, I was able to address my poor sleep and hectic increase in stress at work. Someone else may not be as capable of dealing with these outside stressors. For these people the most important thing is to be aware of these external influences. We’re not robots that just move bars up and down. So many different factors go into determining whether or not you’re going to perform well in the gym or not. Outside stressors have a profound effect, particularly on advanced lifters. I would recommend you back off in training (especially your volume) and a little bit in intensity if necessary as well. Perhaps take an extra rest day between sessions to allow you to recover better. Outside of that, always attend to your form (but you should be doing that anyway). Finally, keep calm! Nothing good comes from getting frustrated and giving up. You have to accept that whilst X stressor is around, recovery resources and adaptation capacity are going to be compromised. But once X stressor becomes less and less or if you adjust your training accordingly, progress can still be made long term.

References:

Nuckols, G. and Isuf, O. (2015) The Science of Lifting.

Yerkes, R. M. and Dodson, J. D. (1908) "The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation",Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18(459–482).

Zourdos, M.C., Klemp, A., Dolan, C., Quiles, J.M., Schau, K.A., Jo, E., Helms, E., Esgro, B., Duncan, S., Merino, S.G. and Blanco, R., 2016.Novel Resistance Training–Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(1), pp.267-275.